I would rank watching Netflix’s latest offering Sex/Life somewhere between getting diarrhea in Barnes and Noble and my annual gyno check-up: awkward, painful, and viscerally embarrassing. I’m no prude — I watched every scene in Bridgerton without blushing and have religiously read Cosmo’s sex tips since the ripe age of 15 — so why did this show in particular make me so uncomfortable? It wasn’t the raunchy sex scenes, or lackluster writing that made it so excruciating to watch — it was the caricature of female sexuality.

Full disclosure, I did not go into the show expecting a world-class examination of the female psyche, but I also did not expect the show that’s been reported as having some of Netflix’s sexiest scenes to be a blatantly obvious male-gaze oriented piece. In arguably the most progressively feminist time in modern history, it’s shocking that a show about sex can be so, well, unsexy.

In the first episode we are introduced to Billie, a well-educated, modern, married woman with an idyllic family; a dedicated, handsome, wealthy husband; and a voracious sexual appetite. Following Freud’s Madonna-Whore complex to a T, the show reveals that Billie’s husband, Cooper, simply cannot view her as sexually desirable as she was before having kids, and expects her sole fulfillment to come from her family. This leaves Billie to reexamine her life and ultimately decide if she can be happy within a situation where she cannot be both her “past” sexual dynamo self and present mother figure.

Struggling to reconcile this truth, Billie begins fantasizing and journaling about her ex-boyfriend. Brad the ex-boyfriend is an exaggeration of everything men think women want: hot, wealthy, successful, and able to seduce any woman with his bad boy antics, sexy accent and cartoonishly huge dick (which you absolutely get to see in a shocking shower scene episode 3). The unpredictable Brad is the foil to Billie’s husband Cooper, who is a devoted father and stable figure in her life—a fact that she is both grateful for and suffocated by, with this familial stability costing Billie her sexual fulfillment.

Reinforcing the idea that Billie can only be a mother or a sexual being is the ongoing theme that Cooper has little to no desire to participate in their sex life. This is clearly demonstrated in episode 2 when he proceeds to watch sports during sex with Billie. When she says he can stop and she can just use her vibrator, he gratefully replies, “really?!”. In fact, the only time Cooper is proactive in their sexual relationship is a patriarchal power play, when he finds Billie’s fantasy-filled journal and feels threatened that she is thinking about a different man.

In this context, it should come as little surprise that only one episode in the entire series passes the Bechdel Test, a “test” to see how feminist a piece of media is. There are three bare-minimum requirements to pass: there are at least two women characters, they speak together, and they speak about anything other than a man. In the solo instance of the last requirement being met in episode 3, Billie is stranded at daycare with her oldest child, who is having trouble adjusting. Billie, who had plans of her own that day and is frustrated at the situation, is then guilt-tripped by another mother for not feeling grateful to spend additional time with her child. Even if, on the surface, this scene passes the “feminist” test, it still serves as a reinforcement of the Madonna-Whore dichotomy, shaming women who find fulfillment outside their children.

With the gratuitous sex scenes sprinkled throughout the episodes, in which you will become more familiar with Billie’s boobs than your own, and the lack of character development, it’s obvious that this show is written in a way that caters to the male gaze rather than a true representation of what women want. Women’s sexuality is a spectrum, with different things empowering different women, a point that this show refuses to acknowledge. Kink and sex-shaming subplots litter the series, such as when Billie and Cooper go to a swinger party in a last-ditch effort to refresh their marriage (spoiler alert: it backfires), Billie not being able to completely honest about her past sexual exploits in fear of being perceived differently by her husband, and treating BDSM practices like choking as explicitly for the non-monogamous.

Outside the melodramatic tropes (Billie being able to “fix” bad boy Brad and turn him to a loving monogamist, and putting BDSM and past sexual preferences in the past to become worthy of love and marriage), most of the show’s main conflict is within Billie herself. Brad acts as a projection of her struggle to fit within the roles she perceives as her only options — either as a wife and mother, or as a free-spirited, sexually liberated individual. I shouldn’t have to say this, but women can be both! Struggling to meld her sexual identity and her status as a matriarch, Billie is presented as a one-dimensional character whose inability to be a multifaceted and complete person ruins both her friendships and her marriage, despite domestic life being what she ultimately chooses to pursue, sacrificing her own needs and wants.

This is a subtle male-centric, patriarchal dig that pursuing her sexuality instead of unquestioningly falling into a Madonna-like mothering role is what destroys her life. Even though boundary-breaking Brad, who attempts to seduce a married woman, and kink-shaming Cooper are equally (if not more so!) to blame. In fact, Billie’s internal confusion about her roles is used as a scapegoat to defend Cooper’s philandering with his boss and with Billie’s friend Trisha at a sex party to make the viewer feel it’s justified when, ironically, any philandering on Billie’s part is purely hypothetical and only in Cooper’s mind.

While I can understand the appeal of Sex/Life at face value, with its salacious sex scenes that as an audience we’re not used to seeing outside porn, it’s hard to ignore the way women’s options for sexual freedom and a fulfilling home life are presented as mutually exclusive. While monogamy may not be for everyone, the idea that it’s a punishment is as almost archaic and played-out as the idea that a woman can only be fulfilled by creating a family. I promise, as a woman, it’s both possible to have your cake in this situation and eat it too.

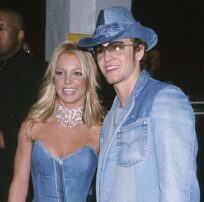

Image: AMANDA MATLOVICH/NETFLIX