I was 7 years old, sitting on top of the toilet seat, hiding, shaking, crying. Every time I closed my eyes I saw flames. “When I die, will I go to Hell?” I asked myself. I said the sinner’s prayer over and over so I would be saved from the fire. “I Admit that I’m a sinner; I Believe that Jesus died for my sins; I Confess that He is my personal Lord and Savior.” I closed my eyes for the hundredth time, but I still saw flames. I stood up shakily as I heard mom yelling from the living room to get dressed. I put on the dreaded pantyhose that made my skin crawl, and the skirt that gave me claustrophobia, and we drove to the church. Sitting there in the audience, my dad hovered above us, preaching from behind the pulpit. He asked, “Do you know where you will go when you die?” The feeling started again, my chest tightened, I shut my eyes; I felt panic. I started whispering, “I admit, I believe, I confess, I admit, I believe, I confess…” In my heart I answered, “Yes, I will go to Heaven.” But then my preacher father asked, “But do you KNOW, that you KNOW that KNOW…

My 7-year-old self suppressed what would be the second panic attack I had on that Sunday. I could feel what seemed like everyone staring at me, and there was ringing silence in my ears. I felt so afraid, and the fear caused me to rise and stand up. The look on my father’s face when I stood was so proud. I looked down at my feet, and they began walking towards the altar. I reached the steps and was embraced by both of my parents, whose eyes were full of tears, lips curled into smiles. They cried, I cried. For a moment, I could breathe. I was saved. I would be in Heaven with my family when I died one day! At bedtime that night, I told my mom I was going to read every page of the Bible, beginning to end, and felt a twinge of guilt that I hadn’t already read the entire book of God’s word. She sweetly smiled and tucked me in. I started in Genesis and read until my eyes began falling. I gave in and closed my eyes tight, clutching my bible to my chest, but to my surprise, the back of my eyelids were not black. I saw a flicker of a flame.

Fast forward 10 years. I was sitting in church as the congregation sang their hearts out to God. The guest preacher for this particular revival left the pulpit and began running around the church. He jumped on top of the seats, and everyone exclaimed and cheered and as he yelled, “The end of the world is coming!” I felt that familiar dread, the familiar panic—what was wrong with me? I looked around and everyone was smiling or crying tears of joy, while my palms felt sweaty.

After the sermon, I approached my youth pastor. “I feel like everyone felt the presence of God, except me,” I admitted to him. “While everyone was singing and crying, I felt nothing.” His response startled me. He said, “You’re not a true Christian unless you truly meant the prayer.” There was my answer: I must not have said the prayer hard enough! I must not have believed with my entire heart! I sat there, once again, as a terrified 17-year-old, and heard the echo of my voice: “I admit, I believe, I confess.”

A month later, I was sitting in the same seat in the church, and my heart was pounding with fear. Everyone was singing, crying, worshipping, and whatever it was that made them feel, I didn’t have. I KNEW in my heart that I meant every word of the prayer. So why didn’t I feel the presence of God? I also knew in my heart that I couldn’t pay attention to a sermon for more than 10 minutes without wondering what it would be like to hold and kiss a girl who I found to be so beautiful. But my daydream was quickly interrupted by the shouting of the word “Homosexuals!” I stopped breathing.

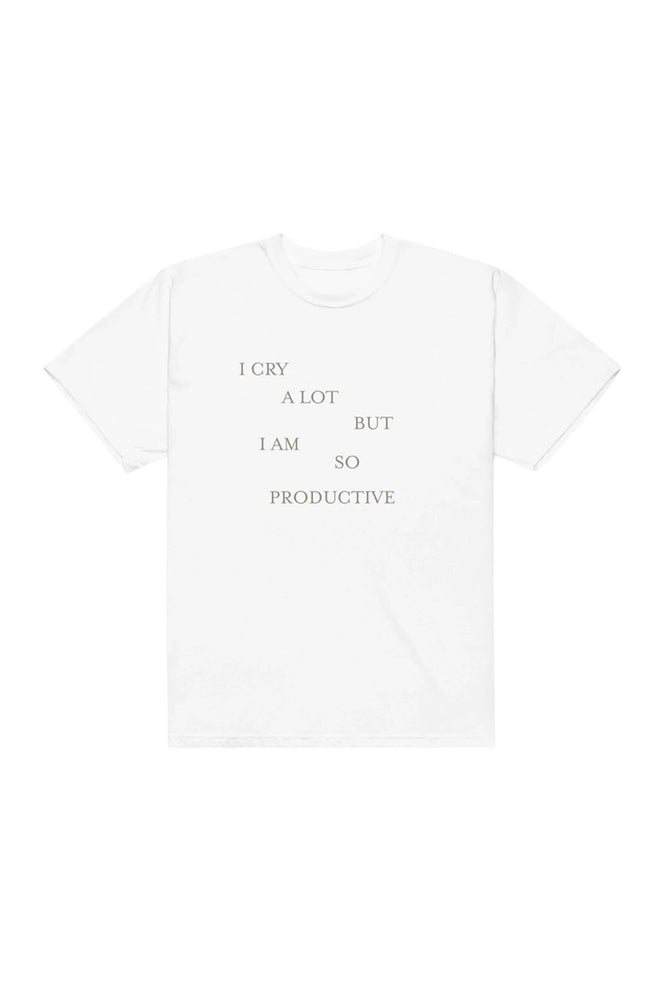

“Homosexuals will not inherit the Kingdom of Heaven,” my dad said. I could hear my own heartbeat ringing in my ears. Almost like a reflex, I snatched a pen and paper and began writing. As my dad spoke, I wrote. As he preached about the eternal fires of Hell, I wrote about my doubts of religion. As he screamed that sinners were going to Hell, I wrote about how maybe my sin wasn’t a sin. The opening line of my scribbling was something to the effect of, “Religion is wrong.” I didn’t know where this was coming from—it was almost like I wasn’t writing it myself—but it was also almost like this was the first time I was ever being truly honest with myself.

My dad finished the sermon, and I went to throw away my writing, but something stopped me. I knew what I had written was wrong, but it felt so personal that I felt like I needed to keep it. I carefully folded the piece of paper into a square and stuck it in my back pocket. I climbed into the pickup truck after my dad, and after we pulled into the driveway of our home, he looked at me and said, “Hand it over.” I felt the piece of paper burning into my backside.

“Ummm, hand what over?”

“You know what I’m talking about,” he said. “You weren’t listening to my sermon, you were being disrespectful and were writing instead. Hand it to me.”

For the first time that I can recall, I spoke back to my father: “No. These are my own personal thoughts.”

We got out of the truck, and he reached into my pocket, pulled it out, and told me to wait in my room while he read it. That was the longest 15 minutes of my life. Each second of the clock felt like the ticking of a bomb.

He came into my room after what seemed like an eternity, grabbed me by the skin under my chin, and said through gritted teeth, “What I tell you is the TRUTH.” He lectured me until after midnight, and when he left the room, all I could do was stare out my window and fantasize how great it would be to open it, slip out, and run as fast as I could as far away as possible. Instead, I pulled out my headphones and began listening to Avril Lavigne.

Now, you have to understand, I was ONLY allowed to listen to Christian music, and Avril Lavigne was not singing about Jesus. A friend had given me the CD, and I had hidden it. That night, I had been pushed to the edge. I couldn’t bear the thought of listening to praise and worship, so I reached for the only thing I owned that wasn’t about God.

And I pushed play—big mistake. An hour later, my dad came back storming into my room and caught me red-handed listening to the music. He yanked it from me and disappeared. He listened to every song on that CD, and then I heard his footsteps coming down the hall. He put the CD in the stereo, and he played each and every song. It was a school night, and it was well past midnight. After each song ended, he would ask, “What is this song about?” I would say, “I don’t know,” and his response would be, “Well it’s not about God, Jesus, or the Holy Spirit…so what is it about?” To which I would have to respond: “Sex, dad.”

This went on for hours—I got maybe an hour or two of sleep before school. My close friend took one look at me and asked what happened. How do you explain to someone that you might be gay, you’re having doubts about your religion, your dad caught you with secular music, if there is a Hell, you’re quite possibly going there, and you were up all night dissecting the hidden meaning of Aril Lavigne’s album? I wanted to tell her everything, run away, and never come back.

A few months later, I finally did hold the hand of that beautiful girl. And when I closed my eyes, I didn’t see the usual spark of a flame— instead, I saw a spark of hope. My stomach and heart burst, I couldn’t stop smiling, and the crippling fear I had lived with my entire life, for a moment in time, completely disintegrated into her soft, beautiful skin. Reaching out for her hand was the single most courageous act I had ever done, and my fingers interlocked with hers as naturally as the air entered my lungs. I risked my entire future, my basketball scholarship, my reputation, and possibly my eternity, for a chance to be close to her, listen to her, and hold her hand.

One day we were caught holding hands, and I knew that life as I had known it would never be the same. I was pulled out of school, my dad threatened to throw me around like a ping pong ball, and my scholarship was taken away. My dad had her come to the house and I died a little when I saw him screaming at my beautiful girl that she had a depraved mind. My dad asked if I had any last words to tell her, and though all I wanted to do was reach out and hold her, I told her what I did was wrong and that I was sorry I had been a bad influence. That I believed in God, and that God thought it was wrong and a sin. I began straight counseling, ran back into the deepest, darkest corner of the closet I could find, and every night I would close my eyes and fear Hell. Every morning I would wake up and fantasize about how to kill myself. Every day I had to prove I was straight, and in my heart—even though holding her hand had been the most beautiful moment of my life—I really did think that it was wrong and that I would go to Hell if I didn’t change. I prayed to change. Every time I had a sinful thought about a girl, I would pull out my bible and read scripture about homosexuals.

Living a fundamentalist lifestyle means there is absolutely no gray area. You live once, you die once, and when you die you go to one of two places, and if you do not live your life according to God’s righteousness, you end up spending eternity in the pits of hell, burning, and you can look up and see your loved ones in the presence of God. This fear is unlike any other fear I can describe. It is crippling. It kept me in the closet. It kept me from living my life. I only felt safe if I was in bible study, if I was in church, and if I was praying—everything outside of that was a threat and therefore could trigger a panic attack. I needed to be saved. I needed to be straight. I needed to change.

But I never did change. Shortly after this incident, I fell in love with a girl in my speech class. I was kicked out of my home because of it. I am not considered a part of the family, and still deal with crippling amounts of sorrow, but not fear. Sorrow that we cannot act be a family because of this fundamental belief that God does not condone homosexuality. I have left the fundamentalist lifestyle and do not believe in the kind of God that I was raised to believe in. I believe that God is love, and it took a decade of unlearning the way of thinking I was taught, and adopting a new way of life.

I remember one night in particular, after being kicked out—it was my first night of freedom. I could do whatever I wanted! I decided to go to Starbucks and study instead of staying in my room all night, as was expected of me in the past. I was doing nothing wrong, just studying for a test, at a Starbucks, but I could not shake the feeling of having to look over my shoulder, of feeling that I was doing something immoral. I was simply having a coffee, but each sip felt like I was slipping into a life of sin. For many years, mundane acts were coated with heavy consequences which were quite simply not real. Having a coffee at 9pm is not inappropriate for a girl in the world. It is not a sin. I had to undo years of wiring to get to a place where I can simply enjoy life.

I have reached that point in my life. I have a deep understanding of love, fear does not have a death grip on me, and I can close my eyes in relief, as love has been the powerful substance to finally put out the flames.

Images: stephaniericemusic / Instagram; Stephanie Rice