During the height of the Black Lives Matter protests against George Floyd’s murder, my boyfriend and I would hear people marching right outside our Downtown Brooklyn apartment. We would rush over to the window to witness these historic rallies. At first, we took enormous pride and appreciation in the fact that thousands of New Yorkers would risk their health—since the pandemic was (and still is) very much a thing—to go to the streets to fight and demand much overdue racial justice and equity.

We would watch these protests every day from afar, which was a paradoxical phenomenon. My boyfriend is a non-U.S. citizen Black man, and I am a Korean-American disabled woman. We felt like we should be out there protesting alongside fellow Brooklynites, but the truth be told, we both were too scared to do so. From a quick periphery scan of the marchers outside the window (our apartment is close to street level), we noticed two observations: no one had a noticeable physical disability. An overwhelming majority of the crowd was white. I knew that my boyfriend and I would feel immense unease and insecurity if we were to join them, especially as brutal police involvement began to escalate.

As I wrote in Teen Vogue earlier this month, “participating in protests and rallies can be taxing and dangerous for people with disabilities under the best circumstances. For example, large crowds can be difficult for Deaf and hard-of-hearing people to navigate. The uneven, narrow, long routes often don’t accommodate people with mobility issues or wheelchair users. All this, combined with the recent reports of the anti-police brutality protests being met with clashes of police brutality, the movement is even less accessible for those with disabilities.”

Disability is the only identity group that literally doesn’t discriminate against other groups: people of all color, gender, sexual orientation, class, and any background could have a disability, and you can acquire a disability at any point in life. Besides women, people with disability make up the largest minority group in America: one in four adults in the country have some disability. Yet, we are the least represented group in mainstream media and news. Even during a time in history where there have been increased efforts of diversity and inclusion, the inclusion and acceptance of disabilities lag significantly behind.

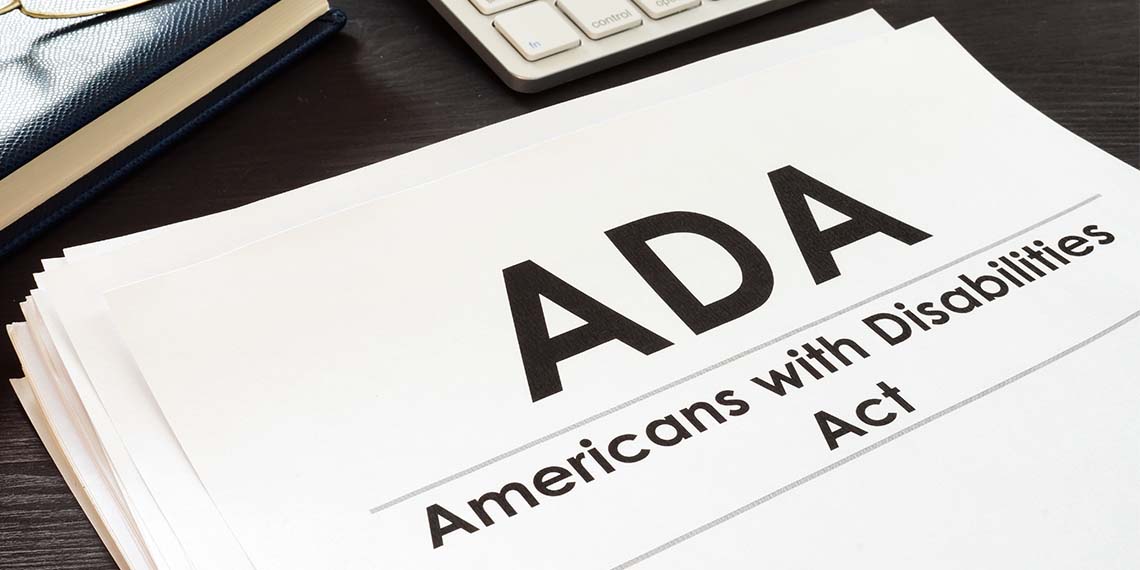

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law on July 26, 1990, marking its 30th anniversary this month. The ADA was the country’s first-ever comprehensive civil rights law for people with disabilities, offering protection against discrimination and imposing accessibility requirements in workplaces and the public. However, equality in theory, unfortunately, does not equate to equality in practice. Disability-related complaints remain among the largest categories filed with government agencies that enforce fair housing and employment laws, and too many buildings and public transportation routes remain mostly inaccessible.

People with disabilities who are a part of other minority groups are even further marginalized in society. For example, suppressed by both ableism and racism, Black disabled people are among the most susceptible to grotesque treatment in this country. Additionally, movements like #MeToo #TimesUp have given millions of women the platform to speak up about their own stories of abuse. Although an overwhelming 80% of disabled women are sexually abused, their voices were not included.

The truth of the matter is that many Americans are probably unaware that July is Disability Pride Month or that this year marks the ADA’s 30th anniversary. The concept of disability pride began to emerge in the early 2000s – it reinforces the idea of accepting and honoring each person’s uniqueness and treating it as another aspect of one’s identity. Perhaps it is because disability activism hasn’t become as trendy as racial justice, LGBTQ+ equality, or feminist movement. The ironic part is that disability is at the intersection of all those issues and then some.

Amid the pandemic outbreak, there has been a surge in anti-Asian harassment, which hit me personally like a double-whammy. My disability has never been entirely accepted in many Asian cultures—in my personal experience, they have been the least receptive of my disability. Asian cultures are notorious for fostering a seemingly unrealistic strive for perfectionism, and having a disability is perceived as being as far from perfect as humanly possible. Growing up as a first-generation Korean-American young woman, I was always told that I should take up the least space possible, and not let my disability be a burden on others. The most significant hurt I’ve received was from Korean adults who thought my cerebral palsy was a curse or sin—those were the very people who were supposed to protect and comfort me. This led me to develop both internalized ableism and racism, which I am still in the process of unlearning today.

So, it truly felt like I was disposed into a dystopian society when, in recent months, I’ve endured disgusting comments from strangers about my race while still receiving micro-aggressions from people of my race. In America, at least we’re making strides to deconstruct that entrenched history of beliefs. Things aren’t moving that progressively in Korea, and, needless to say, in many other Asian countries. For instance, China had a history of abandoning female babies, but now it’s mostly sick and disabled kids who are being thrown away.

In 2020, we are not as progressive as a society as our predecessors probably hoped we would be. Many minority communities are still severely marginalized and don’t have equal representation in any facet of society. Too many white Americans were oblivious to the level of brutality BIPOC face every day. It took the viral spread of an eight-minute video of George Floyd’s death to convince white Americans the level of racial injustice that exists to this day is unruly. Similarly, the global pandemic has proven that the mainstream public is willing to leave the disabled community behind in healthcare; they’re disproportionately impacted by unemployment; students with disabilities are losing their equal access to education.

The well-known mantra within the disability activist community is, “nothing about us without us,” emphasizing that people with disabilities must be integral and essential parts of every human and equal rights movement. Thirty years after the ADA passage, people with disabilities–like myself–are sidelined to society’s outer-most margins. It is not until we are viewed on the same caliber as our peers that we can truthfully say the ADA’s vision has been fully recognized. Whether this takes another 30 or 300 years, that’s up to the rest of society.

Images: Vitalii Vodolazskyi / Shutterstock