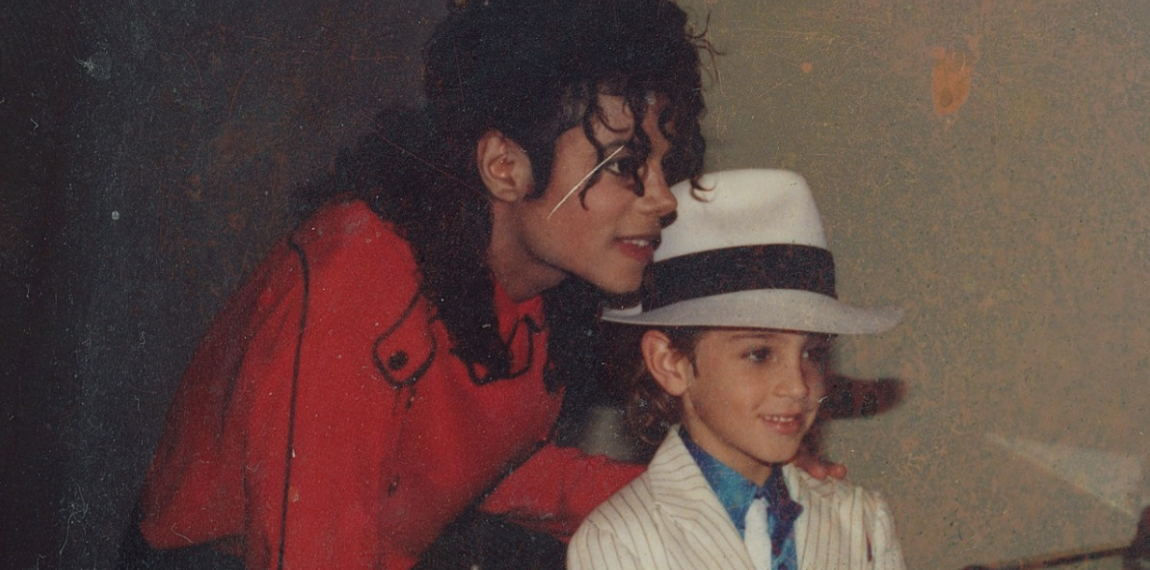

In the past 48 hours, I watched the entirety of Leaving Neverland, director Dan Reed’s two-part, four-hour documentary about two men who claim to have suffered sexual abuse as children, and how they grapple with that trauma to this day. To say I have an emotional hangover would be an understatement—I am sad in ways I didn’t know I could be. While sob-emoji texting my friends, though, I noticed a pattern. When someone hadn’t heard of Leaving Neverland, I clarified: I was watching “the Michael Jackson documentary.” And it’s true—the man accused of sexual abuse in this doc is Michael Jackson, and “Neverland” in the title refers to Jackson’s 2,800-acre ranch, where he allegedly abused an unknown number of prepubescent boys in the ‘90s and 2000s. But having seen the film, I bristle at the idea that this is a Michael Jackson documentary. This is a documentary about child sexual abuse.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BuiE_9qF0PG/[/embed]

Wade Robson and James Safechuck are the two men who tell their stories in Leaving Neverland. Both are indisputably connected to Jackson: Safechuck appeared in a Pepsi commercial with him at the age of 8, and Robson met him at age 5 in Australia, after winning a dance competition. Jackson took a special liking to Safechuck and Robson, and both boys’ relationships with the singer went down similar paths. Jackson would invite the boys’ families on trips, paying for their transportation and lodging, and opening up a world of fame and money they’d never seen before. He told the boys’ mothers that their children were special, that he loved them, and he wanted to help their careers. He said he saw himself in them—and these mothers, dazzled with the vision of raising the next Michael Jackson, struggled to deny Jackson anything.

What Jackson wanted was extended, unsupervised time with their young children. While Robson and Safechuck’s mothers were brought along for many visits to Neverland, they slept in a separate house, and allowed their children to share a bed with Jackson. Safechuck accompanied Jackson on tour; Robson was left alone at Neverland for days at a time. In a 2005 trial for Jackson’s alleged assault of a different 13-year-old boy, it came to light that Jackson would call Robson’s mother at 1am, saying he needed to see Wade right away. Joy Robson (Wade’s mother) would drive him there promptly, and send him straight to Jackson’s bedroom. At the time, the boys insisted that they loved Michael, and he loved them. It wasn’t until they had children of their own that they were able to see the sexual experiences they describe with Jackson—and they describe many—as abuse.

https://twitter.com/JuddApatow/status/1101738418420178944[/embed]

In this moment, it feels surreal to report on these men’s stories of sexual abuse and name the abuser as Michael Jackson. Beyond the shock of hearing these accusations about any beloved celebrity, it feels surreal to name him now because the film focuses so little on the figure of Michael Jackson himself. When you hear “Michael Jackson documentary,” even knowing it’s about allegations of sexual abuse, you expect the film to take on Jackson’s legacy. You expect Jackson to be presented first as an icon: to hear Jackson’s music, or accounts of his persona and cultural impact. Maybe a narrator hyping up how adored he was, before smashing down the hammer of these accusations. But Leaving Neverland does nothing of the sort.

Instead, Leaving Neverland addresses Jackson’s celebrity only in the context of the effect it had on Robson, Safechuck, and their families. It’s important to these stories of sexual abuse to know that Jackson was famous and powerful, because that status informed the parents’ decisions to give him that access to their sons. Similarly, it’s important to hear about how Robson and Safechuck personally admired him: his impact on them as a performer, before they ever met, informed how ecstatic they were when he showed an interest in them; how predisposed they were to admire him and want him in their lives.

https://twitter.com/ambertamblyn/status/1102379571897356288[/embed]

Even clips of Jackson’s performances, or screaming fans, are limited to instances that highlight the trauma it caused to these men. The swarming fans attending Jackson’s tour compounded Safechuck’s sense of being overwhelmed and alone. The line of protesters attending Jackson’s trial played on Robson’s sense of obligation to protect his friend. Leaving Neverland never gives us those images solely to show us that Jackson was beloved, and thus entirely avoids the expected structure for a documentary accused of being “posthumous character assassination.” If Reed’s intention had been (primarily) to shatter the world’s impression of Michael Jackson, I would have expected to first be shown what that impression is—then see it darkly juxtaposed with these men’s stories. Neverland doesn’t feel like the dismantling of a celebrity’s reputation. It feels like two deeply personal accounts of childhood trauma in which their abuser happened to be famous.

https://twitter.com/8675309Carson/status/1102404956760358912[/embed]

Of course, the fact that Leaving Neverland doesn’t explicitly state “here’s proof that Michael Jackson was a child molester” won’t do much to change people’s reactions to the film. Those determined to believe in Jackson’s innocence will do so anyway (though I struggle to understand how, if they take the time to watch the film). And those who believe the stories of Robson and Safechuck will effectively have any lingering fond doubts extinguished. Nonetheless, I think it’s an important and correct choice that Reed focused the film so tightly on these two men and their stories.

Painful as it is for Robson and Safechuck to continue seeing Michael Jackson celebrated, they didn’t strike me as crusaders for his worldwide vilification. They struck me as two men still actively, painfully grappling with the trauma they suffered as children, talking through both what happened and how they behaved in the wake of it. What Leaving Neverland does best, in my opinion, is provide a road map for how this type of abuse can affect people through adulthood, and shed some light on why it’s so difficult for child victims to come forward. And frankly, that’s a much more important story than whether or not a late pop star is deserving of our love.

If you or someone you know is a survivor of sexual abuse, call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800-656-HOPE

Images: HBO; metoomvt / Instagram; juddapatow, ambertamblyn, 8675309Carson / Twitter